You Don’t Need a 3D Camera to Create Depth

Posted: June 25, 2011

Amid all the recent hype over 3D cameras, it’s probably worth noting that creating the illusion of depth in photography is not a novel pursuit. Smart people have been finding clever ways to bring the third dimension into still photos almost since the beginning of the craft.

Amid all the recent hype over 3D cameras, it’s probably worth noting that creating the illusion of depth in photography is not a novel pursuit. Smart people have been finding clever ways to bring the third dimension into still photos almost since the beginning of the craft.

If you’ve ever looked at antique stereo cards using a Stereoscope, for example, you know just how real the 3D illusion can be: You feel as if you can reach in and pluck an apple from a tree.

As a kid, I was addicted to my View-Master 3D viewer. I just couldn’t get enough of those round picture wheels. As far as I was concerned, Mickey Mouse and Pluto were actually hiding inside that viewer.

And so, the technology continues to improve. But the reality is that photographs are inherently two-dimensional; they have height and width, but no depth.

So the appearance of depth will always be an illusion — no matter how we conjure it. In this post, I’ll share some of the visual tricks I use, which work with even the most low-tech cameras.

Depth Cues

Let’s face it: one of the biggest limitations of photographs is that they’re flat.

While a landscape may spread across miles, your photographs are only as deep as the paper they’re printed on. The lack of a third dimension means it’s up to you to create a believable illusion of distance in your photographs.

The reason that we see distance in everyday life is because humans have what is called “binocular vision,” or two separate images overlapping that creates the depth illusion. The ability to sense distance can have some useful applications — like knowing when to stop walking before you walk off the end of a pier or how far to reach to scratch your knee.

While you can’t get such an intense three-dimensional experience from a photograph, there are some visual tricks — known as “depth cues” — you can exploit to enhance the sensation of distance in your photographs.

Knowing how depth is created is particularly useful in landscape photographs because one of the things you’re trying to relate is the physical space involved. So I will focus on landscapes in describing how I use depth cues in my photography.

Linear Perspective

One of the simplest and most direct ways to create a sense of distance in a landscape is to include a leading line, a cue that artists refer to as linear perspective. Highways, fences, rivers, and telephone poles are all things that can take the eye on a deep journey into your image.

Lines are like a siren call to the eye; they beg the eye to follow. It’s hard to look at a photograph that includes a strong lead-in line and not trace its path. It’s the visual equivalent of eating just one potato chip — tough to do!

When these lines are combined with what’s called a “single vanishing point,” the depth illusion gets even stronger. The vanishing point is created whenever all of the lines in a scene appear to be focused on a single spot in the distance.

In the photo below of the military cemetery in St. Augustine, Fla., the lines of the headstones appear to all be heading toward a single vanishing point, making their lure that much stronger.

[caption id="attachment_8688" align="alignnone" width="450"] The lines of the headstones take your eye toward a single vanishing point, making their lure even stronger.[/caption]

The lines of the headstones take your eye toward a single vanishing point, making their lure even stronger.[/caption]

Aerial Perspective

If you’ve ever stood at a scenic overlook gazing out at a mountain range, you’ve probably noticed that the rows of receding peaks seem to get lighter as they get farther away.

This is example of a depth cue called “aerial perspective.” The buildup of haze (or mist or fog) as the peaks get more distant causes the more distant ones to look lighter; the brain interprets this tone change as distance.

The best time to find haze or fog is early or late in the day or just before or after a storm.

While wide-angle lenses are generally better for exaggerating distance in a normal landscape, when it comes to aerial perspective, telephoto lenses (105mm or longer) compress the ever-lightening layers of a subject and further exaggerate the feeling of space. It’s one time when a long lens actually helps create rather than eliminate depth.

Shrinking Sizes

Using our common knowledge of object sizes is another great way to trick the brain into sensing distance.

Since we all know approximately how big a person is, for example, if that person appears as a tiny dot on a beach, we assume there is a great amount of space between the lens and the subject.

Similarly, by contrasting objects of known size — a large person near the camera and a tiny lighthouse in the distance — you are telling the viewer that there is space between the two. Everyone knows that the lighthouse is really much larger than the person.

You can also use shrinking sizes to imply distance by having objects of similar size stretching into the distance.

When you’re sitting in a line of cars waiting to pay the morning toll, the car at the far end of the line seems a lot smaller than the one directly in front of you. We know, of course, that all of the cars are roughly the same size and they’re not really shrinking, but the distance makes them appear to be getting smaller.

[caption id="attachment_8689" align="alignnone" width="450"] Your brain knows these tractors aren't getting physically smaller, so it perceives their apparently diminishing size as distance.[/caption]

Your brain knows these tractors aren't getting physically smaller, so it perceives their apparently diminishing size as distance.[/caption]

Upward Dislocation

Whenever a particular subject is higher in the frame than a nearby one, it appears to us to be farther away. That’s just another trick of our vision system that automatically assumes that things higher in the frame are closer to the horizon and, therefore, farther away.

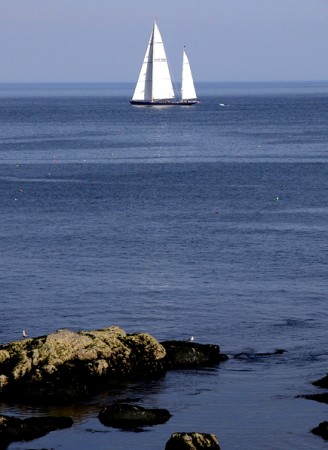

You can exploit this cue easily in a landscape by simply placing one object — such as the sailboat in my shot below — very high in the frame.

[caption id="attachment_8690" align="alignnone" width="328"] We create an illusion of distance by placing the sailboat higher in the frame.[/caption]

We create an illusion of distance by placing the sailboat higher in the frame.[/caption]

Another way to do this, of course, is to aim the lens down to include more foreground space in the frame. By emphasizing the foreground in a beach scene, for example, you create the impression that the beach is very long and the distance to the horizon even greater.

Not all photographs — not even all landscapes — require a sense of distance to be dramatic or realistic. But whenever the perception of distance is important, knowing which cues are available and how to exploit them is a very useful tool.

Biz Tip Source: Black Star Rising

Biz Tip Source: Black Star Rising

Author: Jeff Wignall